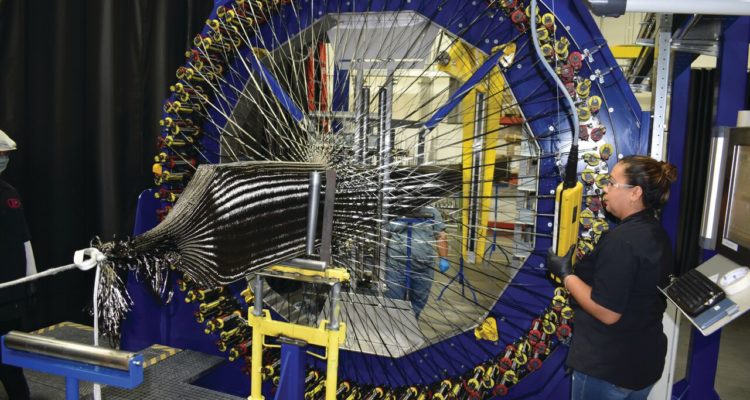

The Composite Recycling Technology Center (CRTC) in Port Angeles, Wash., is testing that feasibility right now in a unique application. The organization has been working since 2015 to create new value from the roughly 50 million pounds of carbon fiber scrap typically sent to landfills. CRTC has manufactured portable pickleball nets, park benches and skateboards, and is now developing wall panels for the construction market.

Together with Washington State University, The University of Minnesota – Duluth Natural Resources Research Institute, USDA Forest Products Lab, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe and Makah Tribe, CRTC has put together an initiative to take coastal western hemlock, thermally modify it and place it in a cross-laminated timber (CLT) that is integrated with recycled carbon fiber supports.

The hemlock achieves mildew, rot and bug resistance, while the carbon fiber adds significant stiffness and strength to the interlocking wall panels, explains Dave Walter, CRTC CEO. “That [integration] allows you to get longer spans in thinner panels than you could just do with wood reinforcement,” says Bridge.

CRTC has built a test panel and is conducting various tests to determine performance. Although the product is not yet commercially available, the patent-pending Advanced CLT system has been specified for the construction of 24 tiny homes, pending funding.

The homes, ranging in size from 240 to 400 square feet, are slated for construction on a 7-acre Port Angeles parcel owned by Pennies For Quarters, a not-for-profit organization working to provide homes for members of the armed forces who have fallen on difficult times and are homeless.

Once a home’s foundation is in place, Walter says that each tiny home can be built in less than three days using the Advanced CLT system. The warm wood walls eliminate the need for drywall and provide a strong, durable and well-insulated home. Each tiny home is projected to achieve an R32 insulation value in the walls and R40 in the ceiling. Ultimately, the project is targeting net-zero energy consumption.

“This is a fantastic opportunity to assist our homeless veterans and show how an under-utilized timber species like coastal western hemlock can be combined with carbon fiber to provide an advanced building material that is very strong and durable,” Walter adds. “The combination of timber and tech is extremely exciting.”

Bridge agrees: “That’s an area I’m watching because it’s an interesting way for composites materials to add some real value in a hybridization format.”

Making a Structural Case

Each of these homes further build the case for use of composite materials in structural applications. It’s a case that needs to be built, as Kreysler finds that the product’s strength-to-weight ratio is often overlooked.

As Kreysler points out, composites are often specified for the stiffness they bring to a specific application. By the time the desired stiffness is achieved, the material is typically strong enough to provide structural benefits as well.

“We’re beginning to utilize composites in what I call a quasi-structural way,” he says. “In other words, making bigger spans between edges or utilizing composites to take advantage of their strengths as well as their durability and formability. That’s where the next big breakthroughs are going to be made.”

Such was the case for “A Gathering Place for Tulsa” in Oklahoma, which Kreysler completed in 2018. The park features a patio with an 8,000-square-foot composite canopy, comprised of 130 sail-shaped, curved panels. (Composites Manufacturing magazine featured the project in its March/April 2017 issue.)

Kreysler created each panel with a polyester resin and fiberglass skin around a balsa core. The resulting roof is stiff enough that the FRP supports itself; vertical steel columns hold the canopy over the patio below, but it’s the only use of structural steel. “Meeting the wind loads required to make that roof stay up was done by the composite material itself, which is unique,” says Kreysler.

More composites fabricators are looking to test these loads. While Janicki Industries has proven that composites are a suitable roofing material on numerous dome projects, the company is now developing a composite monocoque structural roof panel that is infused as a single piece. Bridge notes that applications may include living roofs, where this design could replace existing multi-layer approaches with a single strong, lightweight structure.

Poised for Growth

Composite materials are poised for growth in the architectural industry, and there’s plenty of room for more industry companies to jump on board and support that growth. “The fact of the matter is there are only a handful of people and companies that are really designing and fabricating composites for architecture,” says Ang.

When end users vocalize an oft heard concern – the high cost of composites – manufacturers need to be ready to respond with compelling arguments about the extensive benefits of FRP. The more fabricators that invest in architectural solutions, the more compelling the argument for architects to specify a composite product in their next landmark project.